Josh Grant had no idea how tough it would be to embark on a career when he graduated from Western University with a business degree four years ago. “I got a lot of nos, or no responses, after applying for jobs.”

Employers wanted candidates with corporate experience, even for positions billed as entry-level, Mr. Grant found.

It’s a conundrum that frustrates many new grads: You can’t get a job without experience, and you can’t get experience without a job, as the Royal Bank of Canada and the Canadian Career Development Foundation pointed out in a recent white paper, Addressing the Catch 22.

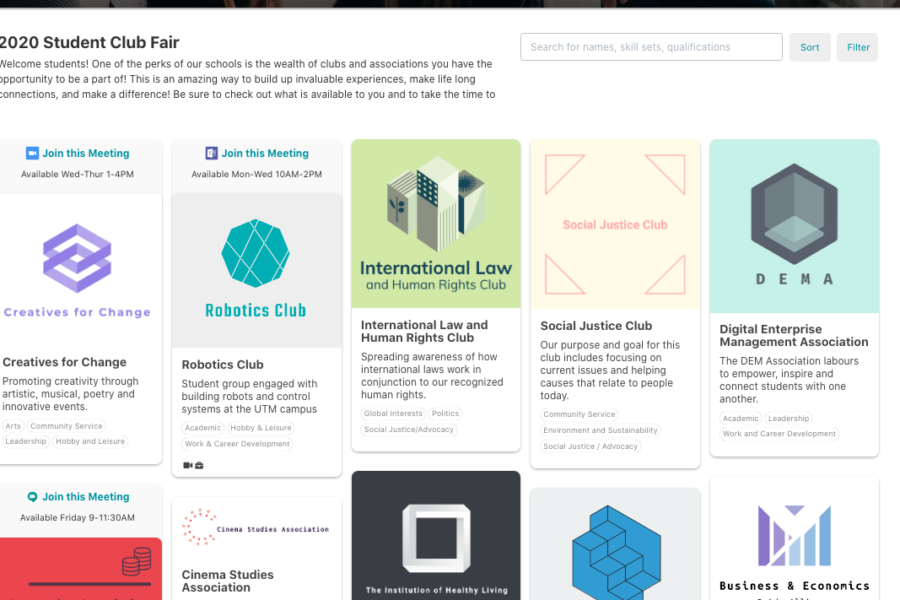

“The transition from school to work is a significant milestone in a young person’s life. It is challenging, difficult and, in this labour market, quite uncertain,” says the report, which drew on the experience of applicants to a unique paid internship established by RBC in 2013. The program is meant to help 100 unemployed and underemployed graduates each year develop the additional skills and work grounding they need to kick-start their careers.

Mr. Grant was among the first group to go through RBC’s Career Launch program. Now 28, he has been working as a social community manager at Corus Entertainment for the past year, constantly updating the various social media platforms. The work is fun, engaging and creative, and he gets to use all his skills, said Mr. Grant, who does not think he would have landed at Corus had RBC not taken a chance on him.

Erine Roberts, 24, was pushed to apply for one of the 2017 internship positions by the Canadian Children’s Aid Foundation, where she volunteers. “They told me, ‘You are wasting your degree.’ You have the education, you have the knowledge, you have the transferable skills, you have a lot to offer.'”

After graduating from Wilfrid Laurier University with the dream of doing social justice and advocacy work, Ms. Roberts “sent out hundreds of resumes, and I got about two calls back.”

Instead, she settled into a full-time job with a high-end retailer. The wages weren’t high, but it was a steady paycheque. Ms. Roberts has also started to wonder if she could even afford to work in some of the not-for-profit positions posted. “It was like, okay, $15 an hour, 30 hours a week but you need a car and you need to have this much insurance. … You would have to get a second job to support the requirements [of the first job] plus housing and paying off the education [loans].”

This is not an unusual scenario for new graduates, said researcher Donnalee Bell, managing director of the Canadian Career Development Foundation.

“They are having a harder time; there are fewer traditional entry-level jobs … so they are finding themselves in more precarious work, more part-time, they are having to cobble together a series of jobs in order to support themselves,” Ms. Bell said.

RBC’s chief human resources officer Helena Gottschling said Canadian universities and colleges are doing a great job of educating the students and more businesses are coming to the realization that it is in their long-term interests to invest in developing the potential of Canada’s future work force.

While many employers still insist on two years of related work experience for entry-level jobs, others are starting to recognize “that the job we are hiring you for today will not be the job you are doing three years from now,” Ms. Gottschling said in an interview.

For his part, Mr. Grant said he would have benefited from doing a work placement while still in school and learning more about how to apply for a job. He neglected to mention volunteer work as a youth group leader on his résumé – because he had been advised to keep it short. “And I had built up a YouTube channel on my own back when I was in school and never thought to leverage that,” he said in an interview.

Both Mr. Grant and Ms. Roberts would also like to see more employers offer something along the lines of RBC’s Career Launch program to give students that crucial first-job experience. The interns are rotated through retail branches, a secondment to a not-for-profit organization and a placement in head office.

“Socially and economically, Canada cannot afford to have more and more graduates get stuck,” the bank and the career development foundation concluded in their Catch-22 report.